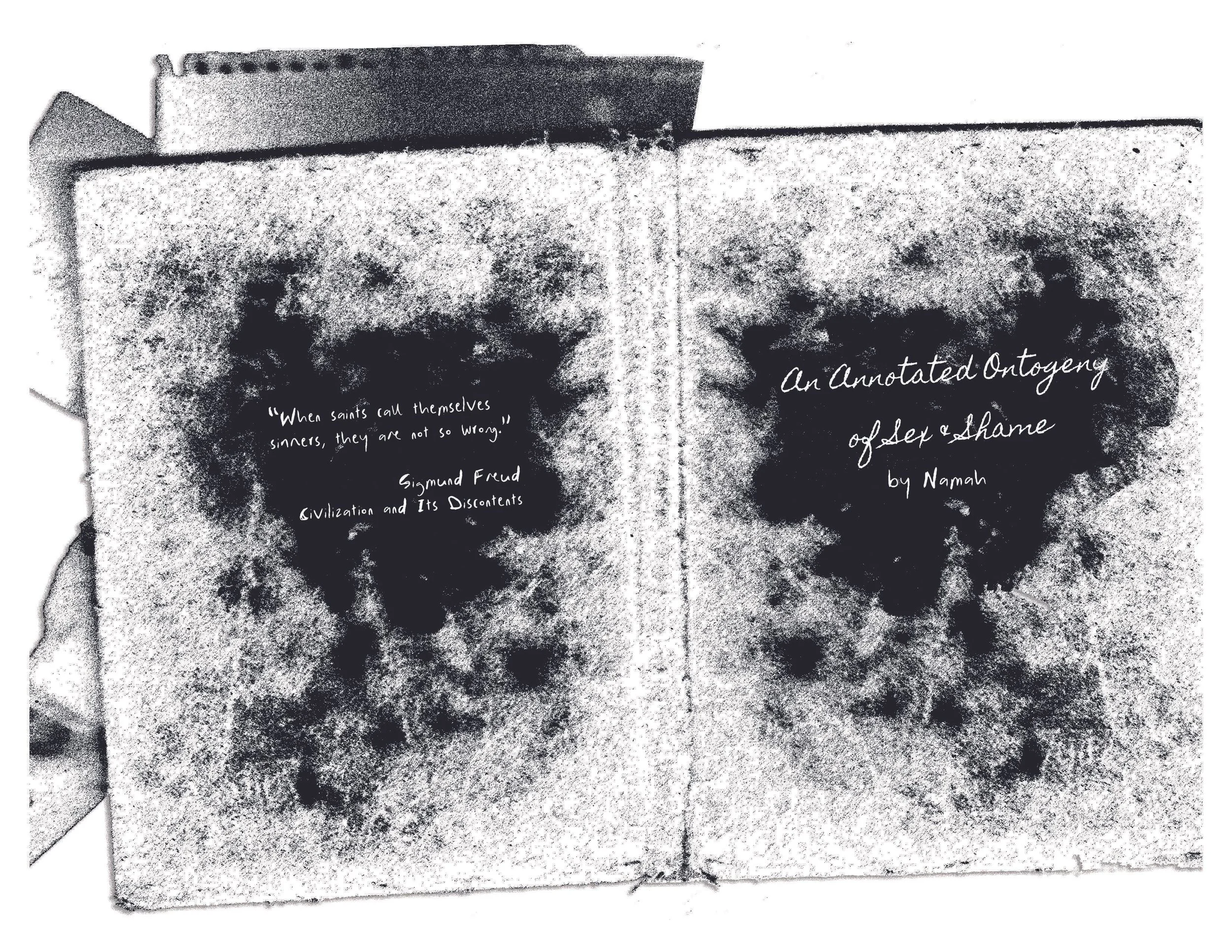

An Annotated Ontogeny of Sex & Shame

by Namah

from Issue 2

Age Six

You are in a car with your parents—it is small

and red and forces you all to crouch close

together. You are driving somewhere sunny and

green and endless. It's a great day. You cannot

think of a better day. What a perfect day! you

keep saying over and over again. When you

arrive at the green pasture, your parents cradle

each hand, occasionally lifting you so that your

feet dangle above the ground, surrounded by

other children whose parents are cradling them

the same way. Everyone is happy and your smile

reaches higher than you ever have on the swing

set. You don’t think you can ever go higher. The

green pasture is mottled with blue— baby birds

that scurry around everywhere, on their own

little walks with their own parents in their own

little concentric circles. You see the other

children kiss them, hold them, claim them as

their own and decide upon the same for yourself.

You grab two that are especially small and soft

and blue and bury them into your chest. You

cannot wait to surprise your parents when you

get home, show them how good you did, show

them how you picked the two bluest birds.

In the car, on the way home, your parents are

bubbling over with praise—What a good girl!

Our perfect baby girl! Our good girl who never

brings us any trouble!, unlike the other children

who begged and pleaded and wore down their

poor, tired parents into taking a bird home. You

feel the smaller of the two flutter against your

chest. This tiny flutter makes your tummy drop

the way it drops when you swing down.

The cramped car, once filled with love, begins to

percolate inch by inch with dread. You grow

catatonic as your parents drone on with praise,

knowing that soon you will be found out,

knowing that soon that which has just been

given to you will be taken away. As your heart

thuds, the bigger of the two buries his beak into

it. Like you, they are growing restless.

You know what needs to be done.

You grab a blue bird, soft and warm and

fluttering still and swallow it whole. You want to

cry as you feel your teeth snap and grind its tiny

bones down but your mouth is too full of

feathers to scream. You leave nothing behind.

Your parents drone on lovingly, stingingly, as

your throat grows so hoarse you are afraid you

will choke. Still, you quiet your breath,

preparing yourself once again to do what needs

to be done. You grab the smaller, softer one that

now looks you in the eye.

You wake up screaming

Despite their best efforts, you still shared a bed with them.

They worked long hours and so, a lacuna like this was a magical rarity.

These units of three remained independently whole, never intersecting.

You now know that there is a natural, predestined way in which one must slowly and cautiously untie themselves from this primordial knot. For a while it struck you to be the most violent severance.

Your impatience developed early and stuck to the roof of your mouth.

You had not yet known the taste of meat.

Shame still feels like feathers in your throat and guilt feelings chewing down bones.

You didn’t talk for days and no one can get you to say why.

Ages Fifteen through Twenty

You’re late. You woke up late and the list of

errands you have to complete mounts and

collapses in your head like a sand dune. You

stuff a flimsy plastic bag full of everything you

think you need and it begins to sag under its own

weight. Big and unwieldy, it collides with every

wall in your way, announcing your arrival,

announcing your disarray. The whole world is a

market, whose anodyne wares you begrudgingly

accept as your own. As the day goes on, more

bags are ladled onto your arms, now long and

thin like a curtain rod, stretching endlessly to

make space for the nameless goods. The bags all

sag under their own weight, and you begin to

sag under theirs. When you get home, you

collapse with the bags that have

begun to feel like overripe fruit leeching off your

rakish arm. You all coalesce into one big rag

pile, a garbage heap in need of disentanglement,

of order, of liberation

So you begin picking apart this dune as swiftly and fruitlessly as a gust of wind—undoing the

disarray only to recast it in a different spot, in a

different shape, in a different shade. And then

you begin again.

From underneath this heap, something

whimpers. At first, you cannot tell what it is or

where it is coming from, muffled under this

cascade of cloth and limb and styrene you call a

home. But you keep digging, and it emerges:

small and shrivelled and afraid like a burdock

burr. Your dog. You forgot you had a dog. You

can’t remember the last time you fed it and now,

in your palms, grey and panting, it looks like it

could crumble like chalk. Hurried, you grab its

neck and force it under the faucet that carves a

stream in your home, hoping that water will

undo what you have done. But its tongue proves

to be too brittle and its limbs are as solid as the

water you beckon it towards. You shake its body

with grief. You scream in your dream.

The heaps in your mind begin to form and

collapse again, like the paltry sighs of the dog's

chest, like the paltry sighs of your own. How

could you have let this happen again?

Or did not sleep

You have no time to stop and think.

These transactions, robbed of any qualia, remind you that excess was never besides the point.

You pledged the world your fealty.

Or pendulous breasts

You still wonder about the difference between the three.

but never distant

This gave your straightening a purpose you did not even realize it needed.

Not the faintest memory.

How long has it been? How long should it have been? You have never actually owned a pet and so, you don’t possess the answers to the questions that keep emerging in your dreams.

But only whimper in your sleep, half turning in your bed.

You dream this dream so often that you begin to startle every time you open your closet.

What kind of beast forgets?

You have no time to stop and think.

Age Twenty Two

You are trapped in a Norman Rockwell painting,

only half erased. You are wearing a full circle

skirt and a half apron, in prints like gingham or

tattersall. You are stirring away in a bakelite

kitchen embellished with every appliance in the

catalog, but something feels wrong. The lights

are too bright and the floor is slanted and so you

are in a battle with the ground that seems to keep

slipping underneath the stem of your heels. The

kettle on the electric stove is roaring, weeping,

sweating and you are afraid it is going to burst.

Instead, the doorbell rings like thunderclap, and

you tremble like a rain cloud. On your doorstep,

on the muddy Welcome mat, is a wrought iron perambulator hiding something cold and wet and

shivering in a swath of cloth. In a flash, you

know somehow that He was Yours.

Under the sheets, he is ugly and mangled like an

intestine. Aborted and deformed. He does not

look like your husband, or really any man you

know, but you cannot be certain because you

cannot bring yourself to look at him for too long.

He emits a low, punctured wail and does not

stop and this makes your stomach ache in a way

that causes the rest of your body to contract,

pushing all your organs into your throat. You go

on stirring in a state of terror as his wail

embalms the kitchen in something waxy and

unmistakable.

The doorbell rings again—it is your husband

home from work, wearing his suit and face like

a wrinkled paper bag. You tremble like a rain

cloud all over again. He sits down on the

kitchen table and you scoop some peas onto the

plate along with the bleeding meat. Your mouth

is full of organs so you do not eat, or talk. You

try to swallow them but you do not have the

stomach for it. You mean to say something, but

you cannot find the words to explain that which

is inexplicable to even you. Instead, your mouth

opens and closes like you are kissing, or gasping

for air.

The kettle still roars. Your husband drags his

polished fork over the pyrex plate, puncturing

his peas one by one, over and over again. The

creature goes on wailing in that same low,

indelible way that makes you want to blow your

brains and does not stop. It is only then that you

realize then that He is yours alone, that He was

always yours alone. You take Him to bed.

Maybe Freedom From Want or Sunday Morning.

The anachronistic nature of this image only adds to your shame.

Something was wrong.

Outside your window, the homeless man screams in agony.

This is how you know He is Yours.

Maybe you are terrified of him.

Maybe you wish not to know his face.

You did not know how to make him stop.

You still cannot bring yourself to murmur the words ‘My baby’ so you just mouth it over and over and over again.

You are unsure if your husband does not see him or simply does not care. You don’t know which is worse.

You think of that wail every time something enters you.

You spend the day alone, soaking and turning in your own sweat.

“Suddenly you will become aware that you are in rags, naked and dusty. You will be seized with a nameless shame and dread, you will seek to find covering and to hide yourself, and you will awake bathed in sweat. This, so long as men breathe, is the plight of the unhappy wanderer.”

Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams